I always felt guilty for bailing on physics in school. As an undergraduate I studied mathematics, but I had enough room left over in my electives to fit in a physics double major if I wanted to. I did this for about a year, and it was going well until I reached the class on Quantum Mechanics. The regular professor for this class was on leave the year I took it, and the substitute had only taught the graduate course, when he had taught at all. This class crushed everyone.

Even as an undergraduate I was a lazy bastard and this was too much hard work, so I dropped QM and jumped into the operating systems class over in the CS department. We developed network protocols for a simple video game in that class rather than try and figure out how to calculate the orbitals of the hydrogen atom. In the long run this served me well, but I always felt like I had copped out intellectually.

The Big Picture

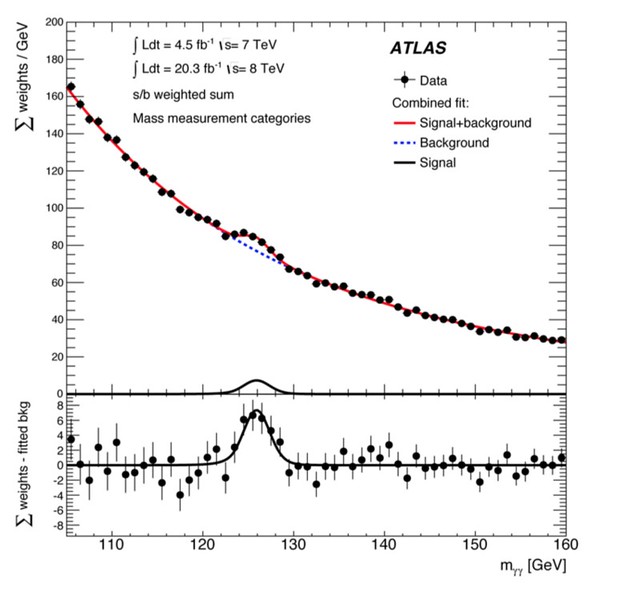

Fast forward to 2012. In 2012 this graph was all over the nerd Internet. It is the reduction of the data that told the physicists that the Higgs boson exists:

The bump tells you that they found the data they wanted. I had read a lot of the popular press accounts of where the Higgs comes from and how the experiments at the LHC were searching for it. One thing that struck me about this search was the heavy use of computing and simulation to both direct the experiments and collect and reduce the data. So I got curious about the nature of this bump and the where our confidence in its meaning comes from.

I should note here that I did not actually expect to figure out this answer on my own and with my limited background. And I certainly wasn’t going to be one of those loons who works out his own theory of everything and then starts pestering real physicists about how the unified theory of quantum gravity is obvious just sitting right in front of them. I approached this project like I approach reading a large body of unfamiliar code, or learning a strange new language/runtime. The trick is to follow a “need to know” heuristic. Don’t try to understand everything at once, that’s impossible. Instead, accept that large swaths of the material will be beyond you, and turn those bits into virtual black boxes. Then pick one or two small questions to understand, and dig into those until you are comfortable, then go back and look again. Most of all let your interest and intuition guide what you investigate more deeply. Over time you will generally find that you start to fill in the gaps of understanding that are within the bounds of what you can practically learn on your own by browsing the Internet.

Things I looked At

Speaking of the Internet, one of the joys of the autodidact on the modern Internet is that you can supplement the relatively abstract activity of reading math papers or text books with the slightly more concrete activity of watching physics professors give lectures. This will often lead you to examples and motivation that are important enough to spend an hour lecture on, but for some reason not important enough to devote ten pages of PDF to in a text book because that PDF for some reason still has to get printed on paper.

Anyway, I’ve been at this for a couple of years now (this is the other nice thing about Internet learning, you can spend as much time at it as you want), and have poked into a wide variety of areas, though none every deeply:

Basic Quantum Mechanics. Here I highly recommend this series of lectures from MIT. Something in this material finally tickled the right parts of my brain and made me able to understand the conceptual framework. In particular, if you want to know what the most important fact about quantum mechanics is, start here. I was proud to be able to answer most of the in-class quiz questions given about 8 or 9 lectures in.

This class by James Binney is also great, but the video on youtube is the wrong aspect ratio. Watch it on iTunes instead. Binney’s book is also one of the better ones, and is nicely typeset even in its Kindle form.

Feynman and QED. This is a remarkable explanation of what is going on. He even illustrates the important role that complex numbers play in the theory in a really clever way.

Entanglement and Bell’s theorem. The short video in the link is a great tutorial. This longer talk is also a great and mostly non-technical discussion of the material. I remember not being able to make heads or tails of this (as it were) in the past, but for some reason it seems much more clear now.

I have poked at Quantum Field Theory a little bit, but have gained no real insight. This material might just be too technical for a faker. A good place to start is with this set of lectures by Tong, from the Perimeter Institute. He also provides a lot of suggestions for other resources. There is also this great historical collection of lectures from the 70s by Sidney Coleman on the subject which are worth watching even if you learn nothing, which you won’t because you can’t read a single thing he writes. But, notice how he smokes in class. Different times.

I also have to give a shout out to the book Quantum field theory for the gifted amateur. I have not worked my way through it all yet, but it is a nice introduction to the material that tries to explain many notations and assumptions that other texts take for granted. Recommended. The Kindle book is also an embedded PDF, which means the math looks good.

The Standard Model. This is actually where I started my top down survey. Stanford has a bunch of video material given by Leonard Susskind, who is a big wig. His lectures on the Standard Model almost reach the point where he tells you something, but you are never quite sure. I was hoping to find a high level but almost mathematical explanation of where the idea for the Higgs field comes from, but never quite got there. I guess I will keep looking.

Special and General Relativity. Special relativity is generally taught in high school and undergraduate physics. So I had seen that before. I always avoided GR because the math seemed too hard. Actually though if you stare at it enough it’s not too hard, and very pretty. Start with Sean Carroll’s notes, and maybe his book too, which is a nice presentation of the subject with (I think) just the right mix of physics and math. More on this subject later.

This series of lectures by Frederic Schuller on the mathematics of GR is very well presented, but perhaps a bit too formal and technical for people with more of a physics bent. You can also go back to the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics and watch a good class there which is more in the “physics style.” There are even multiple years of this class available, which is interesting.

Black holes, and Black Hole Information Theory. This area is sort of a, er, black hole. It is interesting to listen to the theorists worry about bad things happening to black holes that are 100 million times older than the current age of the universe, but I’m not entirely sure it really matters.

Things I Have Learned

A Lot.

For me physics is a constant process of being told that the way you think the world works is wrong. Galileo started the whole thing by figuring out that all matter would move through a vacuum at the same rate. Then Newton told us that an apple falling to the ground and the moon flying around in space are under the influence of the same force. Ludicrous. Then Einstein said that even the idea of absolute space and time is wrong. Sheesh.

I also have some more concrete observations.

Physics Math: Vectors and Tensors

Physicists are well known to be sloppy about the math, and this makes physics books hard to understand. There is an extent to which modern theoretical physics is mostly about the math (although most physicists would disagree with me and hate me for saying it). Mathematical exposition in the physics literature can be really hard to deal with because you are hardly ever told what kind of mathematical object you are reading about at any given time. Instead the physicists generally deal with a relatively small number of abstractions at once, and just assume you will realize which ones belong where by context.

For example, in mathematics vectors are simple objects. They are members of what is called a vector space or linear space. This is a set whose objects obey certain rules of computation.

To make a vector space first you need a set V of vectors and another set of scalar values which is usually either the real numbers (\mathbb R) or the complex numbers (\mathbb C). Then for elements of the vector space v \in V we postulate the following rules:

A scalar multiplied by a vector is a vector, so if v \in V then av \in V for every scalar a.

If w \in V is another vector, then v + w \in V.

If w \in V is another vector, then v + w = w + v.

There is a special vector 0 \in V such that v + 0 = v.

Scalar multiplication and vector addition interact the way you could expect, so like a(v + w) = av + aw and so on.

And some other stuff. I will try not to bore you. The vector space you are all familiar with is the set of real or complex numbers, and the spaces you get when you make finite lists of real or complex numbers, which we call {\mathbb R}^n or {\mathbb C}^n. In elementary physics classes you are then told that vectors are “a magnitude and a direction” and that things like forces, velocities and accelerations are all vectors. And you are left with the idea that these things are just lists of 3 numbers, since space is 3-d (that is, space is modeled by {\mathbb R}^3).

But later on you find out that this is not really how it is. In more complicated mathematics, vectors are what you get by taking derivatives of things (which is what you were doing above to get forces, velocities and accelerations). In {\mathbb R}^3 and other simple spaces these vectors end up being things that you can identify with elements of the same space. But when space gets more complicated, or if you decide to use more complicated coordinate systems this is no longer the case. At this point the simple minded “magnitude and direction” definition is replaced by vague declarations having to do with how objects “transform”. The definitions will read like this: “a vector is an object made up of components with respect to a given coordinate system which transform according to certain rules”, or sometimes just “a vector is an object that transforms like a vector.” Physics people love things that transform correctly. What is never clear is how these objects are related to the things that live in vector spaces in mathematics.

This transform language extends to more complicated mathematical objects too, in particular tensors which are a more complicated kind of matrix-like object that you deal with the most in General Relativity. Again a typical physics definition of a tensor reads like this:

A rank (p,q) tensor T is a set of components (like a matrix) that transform using the following sort of rule when you change coordinate systems:

T^{\mu'_1, \mu'_2, \cdots, \mu'_p}\,{}_{\nu'_1, \nu'_2, \cdots, \nu'_q} = {\partial \mu'_1 \over \partial \mu_1} \cdots {\partial \mu'_p \over \partial \mu_p} {\partial \nu_1 \over \partial \nu'_1}\cdots{\partial \nu_q \over \partial \nu'_q} T^{\mu_1, \mu_2, \cdots, \mu_p}\,{}_{\nu_1, \nu_2, \cdots, \nu_q}.

which just makes the mathematician say what?.

What’s actually going on here is that vectors and tensors really belong to special linear spaces that are made up of functions. The nature of these objects takes a bit of formal background to explain precisely,1 and it is covered in books about differential geometry and related areas. For the physics people it’s easier and quicker to just write down the rules and not think about it. I will not go into this any more now, except to note how similar this is to reading code in a language with no types.

Einstein’s Summation Notation

Another thing that makes learning how to read physics texts difficult is that they leave out summation signs. In relativity you find that you write a lot of sums that look like this

S = \sum_{i=1}^n x_i y^i.

Don’t worry about why some indexes are on top and some on the bottom. That is just another weird convention that everyone understands. Anyway, Einstein’s convention says that whenever you have the same index on the top and bottom in any given term, you can write the sum this way:

S = x_i y^i.

And the sum is implicit. This is sort of like how the “while(<>)” is implicit if you call “perl -n”. In addition in general the indices are understood to always run from 0 to 3, or 1 to 3, or 0 to 2 depending on the context and also whether the indexes are latin (a, b, c, etc) or greek (\mu, \nu, \rho, etc).

This is all fine, but hard to get used to. I still have to stare at formulas for a long time to figure out where sums go.

For example, quick, where do the sums go in this formula?

\Gamma^s_{uv} = {1\over 2}g^{sr}(\partial_u g_{vr} + \partial_v g_{ru} - \partial_r g_{uv})

This might be a trick question, there might not be a sum there at all (actually there is, it’s over the index r).

This notation is also responsible for all the formulas related to relativity and QFT being full of \mu and \nu indices and thus being completely impossible to read and speak (hear it in your mind: “mu nu mu nu nu mu nu mu mu mu nu”).

The Math is Pretty

Although I like to complain about the strange language that physicists use to write mathematics, I also have to admit that mathematics underlying the theories have a certain beauty to them. This is especially true of General Relativity. Sean Carroll’s notes put it best:

General relativity (GR) is the most beautiful physical theory ever invented. Nevertheless, it has a reputation of being extremely difficult, primarily for two reasons: tensors are everywhere, and spacetime is curved … GR can be summed up in two statements: 1) Spacetime is a curved pseudo-Riemannian manifold with a metric of signature (−+++). 2) The relationship between matter and the curvature of spacetime is contained in the equation

R_{\mu\nu} − {1 \over 2}Rg_{\mu\nu} = 8 \pi G T_{\mu\nu}.

However, these statements are incomprehensible unless you sling the lingo. So that’s what we shall start doing.

He’s right. GR is beautiful and it does have a reputation for being difficult to understand. And I’m sure it is difficult to really understand. But if you remember any of your calculus and linear algebra in 3-d space from college I think you can get a taste of the lingo and the beauty. The symmetry of both the theory and the math that describes it is remarkable. Matter curves space, so that curvature must be described a certain way, and that describes how matter moves on the curve. Of course, putting it together was not so purely deductive, but the end result is just perfect.

That’s all I can really say without actually getting into the particulars of the mathematics, and you should probably just read Carroll’s book instead, he’s better at it. Better yet, first read this high level summary of how it all works, then read Carroll’s notes, then maybe his book.

Quantum Mechanics is Weird

Quantum mechanics is different from relativity. Quantum mechanics is strange. It makes you conclude silly things about the world. You shoot electrons through thin slits and find that if you don’t disturb them you get wave-like interference, but if you look at them they turn into bullets. Or, small particles on springs can only have discrete energies, not a continuous range. Or, you can create electrons whose “spins” are related. Note how even the idea of “spin” on a tiny particle that takes up no space is a strange idea. Anyway, you then separate them by miles and when you measure the spin of one at a random angle the other one always ends up in a consistent state even though neither you nor they have any way to know how (see this video).

But, if you are willing to not think about these strange things, the math that describes them is, in its most basic form, fairly elementary. All you need is a comfort with abstract linear algebra and you can understand why (say) the energy levels of the harmonic oscillator are always an integer multiple of \hbar (as explained here, but that’s nine lectures in, some background is needed). It’s really not that hard.

What it is, a bit, is messy and technical, especially if you delve into field theory. And it doesn’t have the inevitability of GR. But it’s fun to play with it until the strange answers seem to make sense, and you see where the waves and bullets come from. Of course, as with GR real understanding takes a lot more work than I’ve put in. I’ve only worked out the very basic aspects of the physics. But it is still neat.

Reading Material

I now realize that I have provided mostly youtube links as opposed to reading material. I guess this makes sense for a page on the Internet. My advice: start with the lecture notes attached to the various videos. They will lead you to larger references. Textbooks are expensive and mostly not available in electronic form … at least not legitimately.

The availability of extensive lecture notes, and even in some cases whole textbooks, on the Internet is a almost as amazing as the youtube material, maybe more so. Some general thoughts on navigating this hoard:

Find a friend who works at a research university and who has library access. Much of the material you want is available to university people for free, but to normal civilians for prices that only organized crime could be proud of. This is especially true of old journal articles that have no business costing $75 per ten page download.

In physics, the stupidity of for-profit academic publishing is to a large extent ameliorated by the existence of the arXiv.org web site where almost all of the recent (since the 90s) literature lives.

Read as many different approaches to a given subject as you can find. Usually if one angle makes no sense, finding a writer who looks at things differently can help. This is especially true when the physicists start leaving out huge bits of math and nothing makes sense. Also, one of the great things about modern physics is the extent to which you can read all the way back to the original material, and much of it is still in a language that is reasonably close to our own.

The math and physics stack exchange sites aren’t bad. Surprisingly.

As I said at the top, follow your intuition and your own interests. The web of knowledge is large and as an Internet Dilettante you have infinite time.

Digression on Blackboards

To me blackboards are the bane of the youtube physics lecture. On the one hand, there is something about the rhythm and pace of information being written on to a blackboard that seems to be just right for actually reading an absorbing the material. Whether this is due to some inherent attribute of the device just our long years of sitting in front of them is unclear to me.

On the other hand, the mechanics of the blackboards are horrible. How many hours of youtube, I wonder, are taken up with professors erasing the boards, or writing the wrong thing on the board, erasing it, and then writing another wrong thing? What is the aggregate time that professors have spent on youtube raising and lowering the blackboards? I’ve seen the most brilliant minds in modern physics utterly defeated by the automatic blackboard movement systems in their lecture halls.

Watching a poor professor staring at his mu’s and nu’s, wondering where the sign went wrong, I fantasize about software that could take his notes and automatically transcribe them to the board, Keynote-animation-like, while he talks over the robot writing. Maybe some enthusiastic graduate student could make a \TeX display system that does this.

I do have two favorite youtube blackboards.

First, in the Frederic Schuller lectures on GR, watch the helpers wet-erasing the boards as the speaker moves from board to board. I’ve never seen real-time wet erasing before.

Second, a shout out to the infinite sheets of blackboards in the lecture halls at Oxford. In the class on basic QM by James Binney it’s a joy every time he grabs a sheet of board and just rolls up into the ceiling, revealing more writing surface down near the floor.

Final Thoughts

I still don’t have a complete explanation for the graph that started this whole thing. In the theory the Higgs (really Higgs, London, Anderson, Englert, Brout, Guralnik, Hagen, and Weinberg) mechanism is an adjustment that they put into the equations describing the “electro-weak” theory. This theory is a set of formulas describing the quantum mechanics of the electromagnetic force (light, magnets, etc) and the “weak” nuclear force (radioactive decay, among other things). The Higgs mechanism takes the form of an additional field (and thus particle) and is needed so that the particles related to carrying the weak force have mass in the theory, and also so the force is short range, since these things are true in real life. Without it the particles would be massless like the photon, and the world as we know it would not exist. Interactions with the Higgs field also give other elementary particles their mass, though how this mechanism works is mysterious to me.

Maybe someday I’ll have some idea about exactly how this works in the mathematics. But, as the nice professor in this video opines, the technical language is pretty obscure and difficult to translate for normal humans, so maybe not. Interesting tidbit (discovered by Phil Anderson, also mentioned in the video): the mathematical framework for this correction also turns up in the theory of superconductivity.

The graph is generated by reducing data from collisions in the LHC. The data is a count of the number of times certain interactions are seen in the collider. The “background” curve is the number of such interactions that would happen if you only count the things we know about, and not the things that the Higgs might cause. The bump means that at a certain energy there are more interactions than you would expect, which is statistical evidence for the existence of a particle, since something must be causing that stuff.

The questions that still stand out for me are: what is the nature of these simulations, and how are they verified? How many total Higgs events were actually observed and measured?2 And just what is it with high energy physicists and Mexican hats? Perhaps in several more years of reading I’ll figure it out. But either way my personal investigation is a nice science project, as it were.

Notes

Tensors are really something called a multilinear function. They take p arguments of one type and q arguments of another type and compute a number. But, the result you get is linear in every argument. This is what generates the transformation rule. Vectors are just tensors that only take one argument.↩︎

Answer (I think): just a couple of hundred out of billions and trillions and trillions.↩︎