The Musical Offering is the sort of Bach that appeals to the mind of a stereotypical engineer. It lives in the wheelhouse of the sort of brain that enjoys abstract complexity and is more comfortable with a bit of emotional distance. So it’s no surprise that it’s my one of my favorite Bach pieces.

The origin of the piece is a fairly well-known piece of lore for music dorks. It seems that King Frederick the Great of Prussia asked Bach to improvise a fugue (a piece of music based on multiple voices playing the variations on a single theme) based on a theme that he made up. You can listen to the theme by playing the first part of this video:

Bach apparently improvised a three part fugue. Perhaps the one played in that recording above. The King then asked him to improvise six voices. Here there are different stories. Wikipedia and Gödel, Escher, Bach both say that Bach demurred and played a fugue based on his own theme. But, this detailed discussion of the piece says he actually did improvise a six part fugue based on the King’s theme.

Whether or not Bach used the King’s theme, I guess the history shows that he did play a six part fugue off the top of his head. To get some idea of what that’s like, here’s a neat visualization of the six part fugue in the Musical Offering that someone programmed a computer to generate:

Imagine improvising something like that.

What everyone agrees on is that Bach went back home and in addition to the three and six part fugues (which he called RICERCARs in an elaborate exercise in acronyms and various plays on words) wrote 10 more canons based on the theme plus a four movement trio sonata. These pieces make up what we now call the Musical Offering.

It’s no surprise that the piece connected with my young engineer brain. As I said in the opening, it is grandly complicated and listening to it is like playing a multi-leveled puzzle in your brain over and over again, as the above video illustrates. In addition to the grand structures of the large fugues, the smaller canons are their own little bits of abstract joy. There are canons where the two voices are inversions of one another. There is another whose pitch seems to modulate up and up and up forever. And so on.

I outlined my first experience with this piece in my story about a needlessly complicated way to play the sound of LP records on a computer. In the early 80s I had just read Gödel, Escher, Bach and this music plays a big role in that book. A book which, by the way, is about the connections between mathematical logic, computer science, artificial intelligence, music, and philosophy. See? Bach is music for dorks.

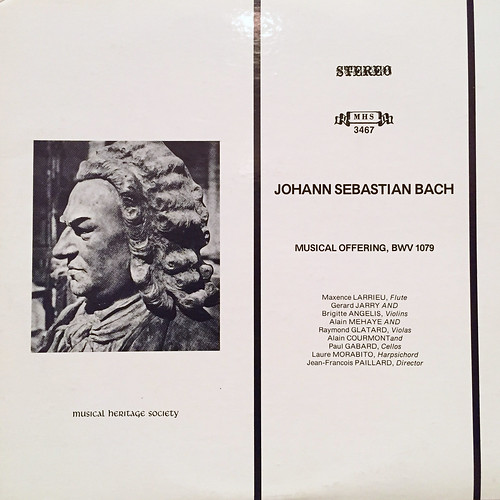

What I remember is reading the book over the summer of my freshman year of college. Then I went home and to my great joy found that my dad had this record:

The Musical Heritage Society was a sort of record club for classical music fans. They licensed records from various sources and put them out under their own umbrella.

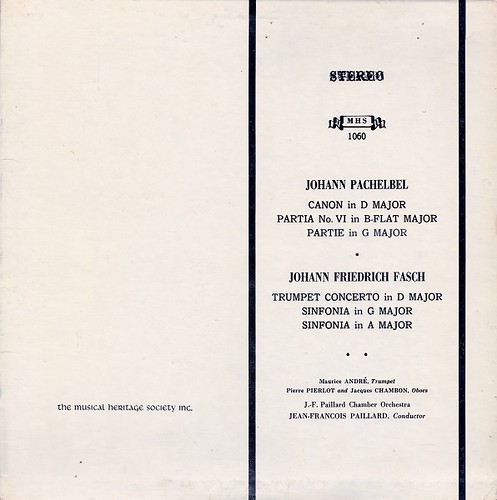

This particular recording was made by a French musician named Jean-Francois Paillard. He was a conductor and musicologist who made many records in the 60s and 70s. His most well-known recording was this one:

You’ve heard this melody, even if you’re not sure you know what it is. If you are skeptical, look it up on youtube.

Paillard made his recordings right at the beginning of the rebirth of interest in baroque music in the late 60s. The musicologists were just beginning to open up the historical record to learn about performance practices and the nature of old instruments. The first step in this process was making more recordings of relatively obscure pieces, but for the most part the records were made with modern instruments and modern instrumental technique. To me this means one thing: the records sound really good.

The Paillard Musical Offering LP was a perennial favorite of mine in the heady 90s when I still had a turntable in the house. I guess I must have played it a lot because my memory of the record is almost perfect. I love the arrangements, especially the emphasis on flute and strings rather than the harpsichord. I guess I’m something of a harpsichord hater, but so many recordings of harpsichords have a harsh and overly bright sound that I just don’t enjoy. The same can be said of old violins played with no vibrato.

When I put my turntable away in the 2000s I figured it would not be that hard to find a nice modern recording of the piece, or maybe even a digital remastering of the MHS LP. But this was not to be. I’ve tried dozens of different recordings, and even bought a few that seemed plausible, but none have the warmth and the charm of the Paillard LP. Instead they tend to be dry, fussy, and academic affairs; more concerned with the fact that the players are using the right instruments than making the instruments make a nice noise.

Anyway, now I have my own digital copy of this recording. It took a few hours and was tedious to make, but I got it all into iTunes and it sounds just as warm and tuneful coming out of my iPhone as it did coming out of my dad’s old turntable when I first found the record thirty years ago. It’s good to have it back.